On the Lagrange Planetary Equations

Introduction

The study of planetary motion has long been a cornerstone of celestial mechanics, offering insights into the dynamics of the solar system. One of the key tools used to describe the motion of planets and other heavenly bodies are the Lagrange Planetary Equations. These equations describe the evolution of orbital elements due to the influence of a general perturbing function. Here we derive these equations. We start with a description of the two-body problem and orbital elements, we then perform an appropriate canonical transform to convert our Hamiltonian into relevant orbital elements. From these, we can derive the effects of a perturbing function, whose form we need not specify.

I. Mechanics

I.I Canonical Transforms

A time-independent coordinate transform \(q_i\rightarrow Q_i\) and \(p_i\rightarrow P_i\) is said to be canonical if it preserves Hamilton’s equations of motion. Specifically, letting the new Hamiltonian \(\mathcal{K}\left(Q_i,P_i\right)=\mathcal{H}\left(q\left(Q_i,P_i\right),p_i\left(Q_i,P_i\right)\right)\), then we have:

\begin{equation} \dot{Q}_i=\frac{\partial\mathcal{K}}{\partial P_i} \end{equation}

\begin{equation} \dot{P}_i=-\frac{\partial\mathcal{K}}{\partial Q_i} \end{equation}

The most useful criteria for determining if a transform is canonical are Poisson brackets. Given coordinates \(q_i\) and \(p_i\), the Poisson bracket of functions \(Q_j\left(q_i,p_i\right)\) and \(P_j\left(q_i,p_i\right)\) is given by: \begin{equation} [ Q_j,P_j ]=\sum_i\frac{\partial Q_j}{\partial q_i}\frac{\partial P_j}{\partial p_i}-\frac{\partial Q_j}{\partial p_i}\frac{\partial P_j}{\partial q_i} \end{equation} It can be shown that a transform is canonical if and only if:

\begin{equation} [ Q_i,Q_j ]=0\label{cannonical 1} \end{equation}

\begin{equation} [ P_i,P_j ]=0 \end{equation}

\begin{equation} [ Q_i,P_j ]=\delta_{ij}\label{cannonical 3} \end{equation}

Poisson Brackets can also be used to determine if a function of coordinates \(f\left(p_i,q_i\right)\) is constant in time: \begin{equation}\label{const function} \frac{df}{dt}=\sum_i\frac{\partial f}{\partial q_i}\dot{q}_i+\frac{\partial f}{\partial p_i}\dot{p}_i=[ f,\mathcal{H} ] \end{equation}

This fact will help us as we study the two and three-body problems.

I.II The Hamilton-Jacobi Equation

A generating function \(F\) generates a canonical transformation from coordinates \(q_i\rightarrow Q_i\) and \(p_i\rightarrow P_i\) and a Hamiltonian \(\mathcal{H}\rightarrow\mathcal{K}\). This generating function satisfies: \begin{equation} p_i\dot{q}_i-\mathcal{H}=P_i\dot{Q}_i-\mathcal{K}+\dot{F} \end{equation} Letting \(F=S\left(q_i,P_i,t\right)-Q_iP_i\), we have: \begin{equation} Q_i=\frac{\partial S}{\partial P_i}\label{transormned position coordinates} \end{equation}

\begin{equation} p_i=\frac{\partial S}{\partial q_i} \end{equation}

\begin{equation} \mathcal{K}=\mathcal{H}+\frac{\partial S}{\partial t} \end{equation} Now, suppose we want our transformed Hamiltonian, \(\mathcal{K}=0\) such that \(\dot{Q}_i=0\) and \(\dot{P}_i=0\). So, we look for a generating function with: \begin{equation}\label{HJ Equation} \mathcal{H}\left(q_i,\frac{\partial S}{\partial q_i},t\right)+\frac{\partial S}{\partial t}=0 \end{equation} This is the Hamilton-Jacobi Equation.

II. Kepler’s Laws

II.I Newton’s Law and Polar Coordinates

We consider two bodies of mass \(m_0'\) and \(m_1'\). Newton’s law of gravitation can be written: \begin{equation} \ddot{\vec{r}}_0’=\frac{\mathcal{G}m_1’}{\parallel \vec{r}_1’-\vec{r}_0’\parallel^3}\left(\vec{r}_1’-\vec{r}_0’\right) \end{equation} \begin{equation} \ddot{\vec{r}}_1’=-\frac{\mathcal{G}m_0’}{\parallel \vec{r}_1’-\vec{r}_0’\parallel^3}\left(\vec{r}_1’-\vec{r}_0’\right) \end{equation} Defining \(\vec{r}=\vec{r}_1'-\vec{r}_0'\), we find: \begin{equation} \label{governing Newton Law} \ddot{\vec{r}} = -\frac{\mathcal{G}m}{\parallel \vec{r}\parallel^3}\vec{r} \end{equation} we have defined \(m\equiv m_0'+m_1'\).

We rewrite \eqref{governing Newton Law} using polar coordinates, with the basis transformation: \begin{equation}

\hat{e}_x=\cos{f}\hat{e}_r-\sin{f}\hat{e}_f \end{equation}

\begin{equation} \hat{e}_f=\sin{f}\hat{e}_r+\cos{f}\hat{e}_f \end{equation} It is not difficult to demonstrate: \begin{equation} \vec{r}=r\hat{e}_e \end{equation}

\begin{equation} \vec{\dot{r}}=\dot{r}\hat{e}_r+r\dot{f}\hat{e}_f \end{equation}

\begin{equation} \vec{\ddot{r}}=(\ddot{r}-{r}\dot{f}^2){\hat{e}_r}+(2\dot{r} \dot{f} + r \ddot{f})\hat{e}_f \end{equation} \eqref{governing Newton Law} becomes: \begin{equation}\label{Netwon polar coordinates} (\ddot{r}-{r}\dot{f}^2){\hat{e}_r}+(2\dot{r} \dot{f} + r \ddot{f})\hat{e}_f = -\frac{\mathcal{G}m}{r^2}\hat{e}_r \end{equation} The norm of the angular momentum vector is given by \(\parallel\vec{r}\times\dot{\vec{r}}\parallel= r^2\dot{f}\). From \eqref{Netwon polar coordinates}, \(\frac{d\left(r^2\dot{f}\right)}{dt}=0\), a statement of the conservation of total angular momentum. Let us define the reduced mass: \(\mu\equiv\frac{m_0'm_1'}{m_0'+m_1'}\), and defined the quantity \(L\equiv\mu\parallel\vec{r}\times\dot{\vec{r}}\parallel=\mu r^2\dot{f}\).

II.II Kepler’s First Law

We rewrite \eqref{Netwon polar coordinates} in the \(\hat{e}_r\) direction:

\begin{equation}\label{r equation newton} \ddot{r}-\frac{L^2}{\mu^2r^3}=-\frac{\mathcal{G}m}{r^2} \end{equation}

Performing the substitution, \(u=\frac{1}{r}\):

\begin{equation} \dot{r} = \dot{u}\frac{dr}{du} = -r^2\dot{u} = -r^2\dot{f}\frac{du}{df} = -\frac{L}{\mu}\frac{du}{df} \end{equation}

\begin{equation} \ddot{r} = \frac{d}{dt}\left(-\frac{L}{\mu}\frac{du}{df}\right)=–\frac{L}{\mu}\dot{f}\frac{d^2u}{df^2} = -\left(\frac{L}{\mu}\right)^2u^2\frac{d^2u}{df^2} \end{equation}

\eqref{Netwon polar coordinates} in terms of \(u\):

\begin{equation} \label{dif eq with u} -\left(\frac{L}{\mu}\right)^2u^2\frac{d^2u}{df^2} -\frac{L^2}{\mu^2r^3} = -\mathcal{G}mu^2 \quad\rightarrow\quad \frac{d^2u}{df^2} + u = \mathcal{G}m\frac{\mu^2}{L^2} \end{equation}

Solving for \(u\):

\begin{equation} u=\mathcal{G}m\frac{\mu^2}{L^2}\left(1+e\cos{f}\right) \end{equation}

Where \(e\) is a dimensionless parameter, the eccentricity which we are free to set. Solving for \(r\):

\begin{equation}\label{r equation kepler} r=\frac{L^2}{\mathcal{G}m\mu^2}\frac{1}{1+e\cos{f}} \end{equation}

We consider only \(0<e<1\), giving a closed orbit. Broadly speaking, the closer \(e\) is to 0, the more circular an orbit is, and as \(e\) approaches 1, the orbit becomes more elliptical. This is Kepler’s First Law. Note that because \(e\) is a constant we chose, \(\dot{e}=0\).

II.III Kepler’s Third Law

We relate the orbit period \(P\) with the orbit’s semi-major axis \(a\). Converting \eqref{r equation kepler} into Cartesian coordinates:

\begin{equation} r+ex=\frac{L^2}{\mathcal{G}m\mu^2}\quad\rightarrow\quad y^2=\left(\frac{L^2}{\mathcal{G}m\mu^2}-ex\right)^2-x^2 \end{equation}

We find the length \(l\), of the orbiting ellipse by adding the zeros of our ellipse:

\begin{equation} l= \frac{L^2}{\mathcal{G}m\mu^2}\frac{1}{e+1} - \frac{L^2}{\mathcal{G}m\mu^2}\frac{1}{e-1} = \frac{2L^2}{\mathcal{G}m\mu^2}\frac{1}{1-e^2} \end{equation}

The semi-major axis \(a\) is defined as half this length:

\begin{equation}\label{a equation} a=\frac{L^2}{\mathcal{G}m\mu^2}\frac{1}{1-e^2} \end{equation}

The height, \(h\), of our ellipse is given by the maximum of y:

\begin{equation} h=\frac{L^2}{\mathcal{G}m\mu^2}\frac{1}{\sqrt{1-e^2}} \end{equation}

Finding the area, \(A\), of the ellipse:

\begin{equation} A=\pi\frac{lh}{2}=\pi\left(\frac{L^2}{\mathcal{G}m\mu^2}\right)^2\left({1-e^2}\right)^{-\frac{3}{2}}=\pi\sqrt{\frac{L^2}{\mathcal{G}m\mu^2}}a^{\frac{3}{2}} \end{equation}

Using Kepler’s second law, which is easily found by considering the area swept out in our ellipse over time:

\begin{equation} \dot{A} \simeq \frac{1}{2}r^2\dot{f} = \frac{L}{2\mu} \end{equation}

We can find the period \(P\):

\begin{equation} P=\frac{A}{\dot{A}}=\frac{2\pi a^{\frac{3}{2}}}{\sqrt{\mathcal{G}m}} \end{equation}

We define the mean motion at \(n=\frac{2\pi}{P}\) and summarize Kepler’s Laws:

\begin{equation} n=\sqrt{\frac{\mathcal{G}m}{a^3}}\label{n equation} \end{equation} \begin{equation} L=\mu\sqrt{\mathcal{G}ma\left(1-e^2\right)}=\mu na^2\sqrt{1-e^2}\label{L defintion} \end{equation} \begin{equation} r=\frac{a\left(1-e^2\right)}{1+e\cos{f}}\label{r theta equation} \end{equation}

III. Orbital Elements

III.I Derivation of Mean and Eccentric Anomalies

From \eqref{r theta equation}:

\begin{equation} \dot{r} = \frac{r}{1+e\cos{f}}e\sin{f}\dot{f}=\frac{L}{\mu r\left(1+e\cos{f}\right)}e\sin{f}=\frac{na^2\sqrt{1-e^2}}{r\left(1+e\cos{f}\right)}e\sin{f} \end{equation}

We have used \(L=\mu r^2\dot{f}\) and \eqref{L defintion}. Again using \eqref{r theta equation}:

\begin{equation} \dot{r} = \frac{na}{\sqrt{1-e^2}}e\sin{f} \end{equation}

In polar coordinates, the magnitude of the velocity vector \(\parallel\dot{\vec{r}}\parallel^2=\parallel\vec{v}\parallel^2=\dot{r}^2+r^2\dot{f}^2\), resulting in:

\begin{equation} v^2=\dot{r}^2+\frac{L^2}{r^2\mu^2}=\frac{n^2a^2}{1-e^2}e^2\sin^2{f}+\frac{n^2a^2}{1-e^2}\left(1+e\cos{f}\right)^2=\frac{n^2a^2}{1-e^2}\left(1+2e\cos{f}+e^2\right) \end{equation}

With \eqref{r theta equation} and \eqref{n equation}:

\begin{equation}\label{v^2 equation} v^2=\frac{n^2a^2}{1-e^2}\left(\frac{2a(1-e^2)}{r}-1+e^2\right)=\frac{2n^2a^3}{r}-n^2a^2=\mathcal{G}m\left(\frac{2}{r}-\frac{1}{a}\right) \end{equation}

Using \eqref{v^2 equation} to rewrite \(\dot{r}\):

\begin{equation}\label{r dot equation} \dot{r}^2=v^2-\frac{L^2}{r^2\mu^2}=\frac{2n^2a^3}{r}-n^2a^2-\frac{ n^2a^4\left(1-e^2\right)}{r^2}\quad\rightarrow\quad \dot{r}=\frac{na}{r}\sqrt{a^2e^2-\left(r-a\right)^2} \end{equation}

We have a differential equation for \(r\), which we solve by writing \(r\) in terms of the eccentric anomaly \(E\):

\begin{equation} r=a\left(1-e\cos{E}\right)\label{r E equation}\end{equation} \begin{equation} \dot{r}=ae\sin{E}\dot{E} \end{equation}

Rewriting \eqref{r dot equation} using \(E\):

\begin{equation} \dot{E}=\frac{na}{r}=\frac{n}{1-e\cos{E}} \end{equation}

Integrating, we find:

\begin{equation}\label{Kepler eq} E-e\sin{E}=n\left(t-t_0\right)\equiv\mathcal{M} \end{equation}

This is Kepler’s Equation, where \(\mathcal{M}\) is known as the mean anomaly.

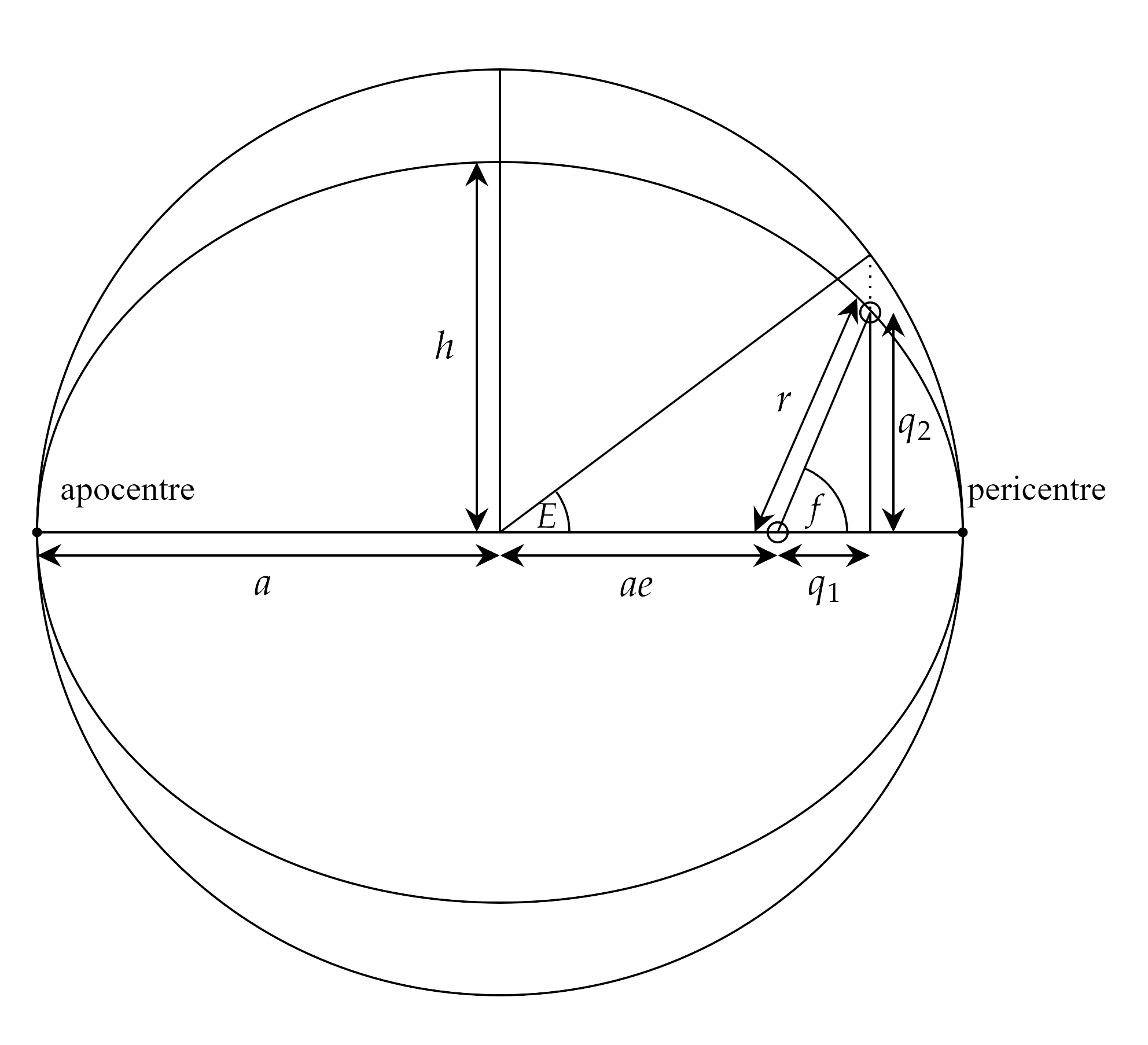

III.II Two-Dimensional Orbital Elliptical Elements

From our orbital element diagram, we can immediately conclude: \begin{equation}\label{cos f equation} Q_1=r\cos{f}=a\cos{E}-ae \end{equation} From \eqref{r theta equation}: \begin{equation} r=\frac{a(1-e^2)}{1+e\cos{f}}=\frac{ra(1-e^2)}{r+eQ_1}=\frac{ra(1-e^2)}{r+e\left(a\cos{E}-ae\right)} \end{equation} \begin{equation} \rightarrow\quad r=a(1-e^2)-e\left(a\cos{E}-ae\right)=a\left(1-e\cos{E}\right) \end{equation} Aligning with our result of \eqref{r E equation}. We can also calculate \(Q_2\): \begin{equation} Q_2=\sqrt{r^2-Q_1^2}= a\sqrt{\left(1-e\cos{E} \right)^2 - \left(\cos{E}-e \right)^2} = a\sqrt{1-e^2}\sin{E} \end{equation} In summary: \begin{equation} Q_1=a\left(\cos{E}-e\right)\label{Q_1 eq} \end{equation} \begin{equation} Q_2=a\sqrt{1-e^2}\sin{E}\label{Q_2 eq} \end{equation} \begin{equation} r=a\left(1-e\cos{E}\right) \end{equation}

III.III Three-Dimensional Orbital Elements

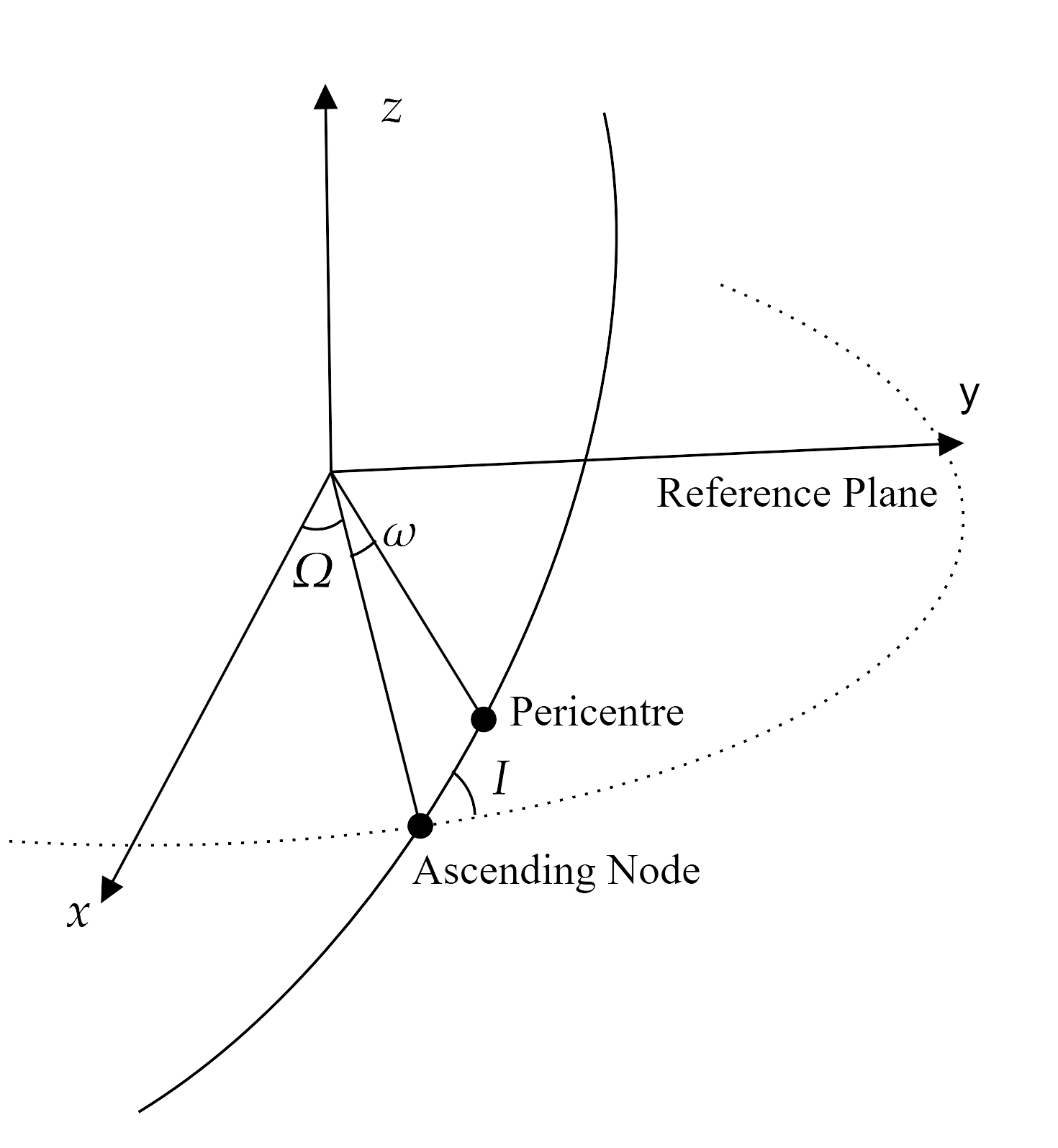

To characterize the orientation of our ellipse in three-dimensional space with respect to a reference plane \(x,y,z\), we introduce three new angles. The first is the inclination \(i\), describing the tilt of the orbiting ellipse with respect to the \(x,y\) plane. Any orbit with a nonzero inclination will intersect the reference plane at two points. The ascending node is the point at which the body passes from negative \(z\) to positive \(z\), and the descending node is the opposite. The angle between the ascending node with the \(x\) axis is the longitude of the ascending node, noted by \(\Omega\). Finally, \(\omega\), the argument of the pericentre determines the angle from the \(x,y\) of the pericentre along the orbiting plane.

Schematically, the transformation from a vector \(\vec{r}\) in the reference plane to a vector \(\vec{q}\) in the orbiting ellipse can be thought of as three consecutive rotations. First, we rotate around the \(z\) axis by \(\Omega\) to align the \(x\) axis with the ascending node. Then we rotate around the \(x\) axis by \(I\) to set the \(z\) axis normal to the orbiting plane. Lastly, we rotate around the \(z\) axis by \(\omega\) to set the \(x\) axis along the semi-minor axis. In summary, we define the rotation:

\[\begin{equation} \begin{pmatrix} x \\ y \\ z \\ \end{pmatrix} = \begin{pmatrix} \cos{\Omega} & -\sin{\Omega} & 0\\ \sin{\Omega} & \cos{\Omega} & 0\\ 0 & 0 & 1 \\ \end{pmatrix} \begin{pmatrix} 1 & 0 & 0\\ 0 & \cos{I} & -\sin{I}\\ 0 & \sin{I} & \cos{I}\\ \end{pmatrix} \begin{pmatrix} \cos{\omega} & -\sin{\omega} & 0\\ \sin{\omega} & \cos{\omega} & 0\\ 0 & 0 & 1 \\ \end{pmatrix} \begin{pmatrix} Q_1 \\ Q_2 \\ Q_3 \\ \end{pmatrix} \end{equation}\] \[\begin{equation} \vec{r}=\bf{R}_{\Omega} \bf{R}_I \bf{R}_{\omega} = \bf{R}_{xq} \vec{q} \end{equation}\]The matrix \(\bf{R}_{xq}\) transforms \(\vec{q}\) to \(\vec{r}\) and \(\bf{R}_{qx}=\bf{R}_{xq}^{-1}\) does the inverse.

\[\begin{equation} \bf{R}_{xq}= \begin{pmatrix} \cos{\Omega}\cos{\omega}-\sin{\Omega}\cos{I}\sin{\omega} & -\cos{\Omega}\sin{\omega}-\sin{\Omega}\cos{I}\cos{\omega} & \sin{\Omega}\sin{I}\\ \sin{\Omega}\cos{\omega}+\cos{\Omega}\cos{I}\sin{\omega} & -\sin{\Omega}\sin{\omega}+\cos{\Omega}\cos{I}\cos{\omega} & -\cos{\Omega}\sin{I}\\ \sin{I}\sin{\omega} & \sin{I}\cos{\omega} & \cos{I} \\ \end{pmatrix} \end{equation}\]From \eqref{Q_1 eq} and \eqref{Q_2 eq}, and because the orbit is by definition in the orbiting ellipse setting \(Q_3=0\):

\[\begin{equation} \vec{q}= \begin{pmatrix} a\left(\cos{E}-e\right)\\ a\sqrt{1-e^2}\sin{E}\\ 0 \\ \end{pmatrix} \end{equation}\]Utilizing our transform and polar coordinates, \(Q_1=r\cos{f}\), \(Q_2=r\sin{f}\): \begin{equation} \frac{x}{r}=\left(\cos{\Omega}\cos{\omega}-\sin{\Omega}\cos{I}\sin{\omega}\right)\cos{f}+\left(-\cos{\Omega}\sin{\omega}-\sin{\Omega}\cos{I}\cos{\omega}\right)\sin{f}\nonumber \end{equation} \begin{equation} =\cos{\Omega}\cos{(\omega+f)}-\sin{\Omega}\cos{I}\sin{(\omega+f)}\label{x orbital elements} \end{equation} \begin{equation} \frac{y}{r}=\left(\sin{\Omega}\cos{\omega}+\cos{\Omega}\cos{I}\sin{\omega}\right)\cos{f}+\left(-\sin{\Omega}\sin{\omega}+\cos{\Omega}\cos{I}\cos{\omega}\right)\sin{f}\nonumber \end{equation} \begin{equation} =\sin{\Omega}\cos{(\omega+f)}+\sin{\Omega}\cos{I}\cos{(\omega+f)}\label{y orbital elements} \end{equation} \begin{equation} \frac{z}{r}=\sin{I}\sin{\omega}\cos{f}+\sin{I}\cos{\omega}\sin{f}\nonumber \end{equation} \begin{equation} =\sin{I}\sin{(\omega+f)}\label{z orbital elements} \end{equation}

IV. Expansion of the Two-Body Hamiltonian in Delaunay Variables

Here we write the Hamiltonian for the two-body system and solve the Hamilton-Jacobi Equation to find a set of action-angle variables that are constant over time.

We begin by identifying the Two-Body Hamiltonian in Cartesian coordinates. From \eqref{governing Newton Law}, the Lagrangian of the system is given by: \begin{equation} \mathcal{L}=\frac{1}{2}\mu\parallel\dot{\vec{r}}\parallel^2+\frac{\mathcal{G}\mu m}{\parallel\vec{r}\parallel} \end{equation} Via the Euler-Lagrange Equation, \eqref{governing Newton Law} is recovered: \begin{equation} \frac{d}{dt}\left(\frac{\partial \mathcal{L}}{\partial \dot{\vec{r}}}\right)-\frac{\partial \mathcal{L}}{\partial \vec{r}}=0\quad\rightarrow\quad\mu\ddot{\vec{r}}+\frac{\mathcal{G}\mu m}{\parallel\vec{r}\parallel^3}\vec{r}=0 \end{equation} We can now write the Hamiltonian using:

\begin{equation} \vec{p}=\frac{\partial \mathcal{L}}{\partial \dot{\vec{r}}}=\mu\dot{\vec{r}}\label{p def} \end{equation}

\begin{equation} \mathcal{H}=p\dot{r}-\mathcal{L}=\frac{1}{2\mu}\parallel\vec{p}\parallel^2-\frac{\mathcal{G}\mu m}{\parallel\vec{r}\parallel} \end{equation}

From the spherical symmetry of the problem, it is natural for us to proceed using spherical coordinates. We perform another canonical transform from \(p_x\), \(p_y\), \(p_z\), \(r_x\), \(r_y\), and \(r_z\) coordinates to \(p_r\), \(p_\phi\), \(p_\theta\), \(r\), \(\theta\), and \(\phi\) coordinates:

\begin{equation} r_x = r \cos{\phi} \sin{\theta} \label{polar transform start} \end{equation}

\begin{equation} r_y = r \sin{\phi} \sin{\theta} \end{equation}

\begin{equation} r_z = r \cos{\theta} \end{equation}

\begin{equation} p_x = p_r \cos{\phi} \sin{\theta} - \frac{p_\phi}{r \sin{\theta}} \sin{\phi} + \frac{p_\theta}{r} \cos{\phi} \cos{\theta} \end{equation}

\begin{equation} p_y = p_r \sin{\phi} \sin{\theta} + \frac{p_\phi}{r \sin{\theta}} \cos{\phi} + \frac{p_\theta}{r} \sin{\phi} \cos{\theta} \end{equation}

\begin{equation} p_z = p_r \cos{\theta} - \frac{p_\theta}{r} \sin{\theta} \end{equation}

\begin{equation} p_r = \sqrt{p_x^2 + p_y^2 + p_z^2} \label{polar transform end} \end{equation}

Again, it can be shown that this transform satisfies \eqref{cannonical 1}-\eqref{cannonical 3}. The Hamiltonian becomes: \begin{equation}\label{2 body cartesian hamiltonian} \mathcal{H}=\frac{1}{2\mu}\left(p_r^2+\frac{p_\theta^2}{r^2}+\frac{p_\phi^2}{r^2\sin^2{\theta}}\right)-\frac{\mathcal{G}\mu m}{r} \end{equation}

IV.I Action-Angle Variables

We now find a canonical transform, \(q_i\rightarrow Q_i\) and \(p_i\rightarrow P_i\) such that our transformed Hamiltonian \(\mathcal{K}\) is a function of only momenta, \(\mathcal{K}\left(P_i\right)\). Transformed position coordinates are known as angles and transformed momenta are known as actions.

Utilizing the Hamilton-Jacobi Equation \eqref{HJ Equation} with a generating function \(S\left(r,\theta,\phi;P_1,P_2,P_3;t\right)\), where \(P_1\), \(P_2\), and \(P_3\) are constants of motion because the transformed Hamiltonian \(\mathcal{K}\) is independent of \(Q_i\). The Hamilton-Jacobi Equation is: \begin{equation} \frac{1}{2\mu}\left(\left(\frac{\partial S}{\partial r}\right)^2+\frac{1}{r^2}\left(\frac{\partial S}{\partial \theta}\right)^2+\frac{1}{r^2\sin^2{\theta}}\left(\frac{\partial S}{\partial \phi}\right)^2\right)-\frac{\mathcal{G}\mu m}{r}+\frac{ \partial S}{\partial t}=0 \end{equation} Separating \(S\): \(S\left(r,\theta,\phi;P_1,P_2,P_3;t\right)=S_r\left(r;P_i\right)+S_\theta\left(\theta;P_i\right)+S_\phi\left(\phi;P_i\right)+S_t\left(P_i;t\right)\), we find: \begin{equation} \frac{1}{2\mu}\left(\left(\frac{dS_r}{dr}\right)^2+\frac{1}{r^2}\left(\frac{dS_\theta}{d\theta}\right)^2+\frac{1}{r^2\sin^2{\theta}}\left(\frac{dS_\phi}{d\phi}\right)^2\right)-\frac{\mathcal{G}\mu m}{r}+\frac{S_t}{dt}=0 \end{equation} We find: \begin{equation} \frac{dS_t}{dt} = -P_1 \label{S_t derivative} \end{equation}

\begin{equation} \frac{dS_\phi}{d\phi} = P_2 \end{equation}

\begin{equation} \left(\frac{dS_\theta}{d\theta}\right)^2 + \frac{P_2^2}{\sin^2\theta} = P_3^2 \end{equation}

\begin{equation} \left(\frac{dS_r}{dr}\right)^2 + \frac{P_3}{r^2} - \frac{2\mathcal{G}\mu^2 m}{r} = 2\mu P_1 \label{S_r derivative} \end{equation}

Now we identify the three constants of motion, \(P_1\), \(P_2\), and \(P_3\). As \(\frac{\partial \mathcal{H}}{\partial t}=0\), the energy of the system is conserved. \begin{equation} P_1=\frac{1}{2\mu}\left(p_r^2+\frac{p_\theta^2}{r^2}+\frac{p_\phi^2}{r^2\sin^2{\theta}}\right)-\frac{\mathcal{G}\mu m}{r} \end{equation} The total angular momentum of the system: \begin{equation} P_3^2=p_\theta^2+\frac{p_\phi^2}{\sin^2{\theta}} \end{equation} and the angular momentum along the \(z\) axis: \begin{equation} P_2=p_\phi \end{equation} are also conserved. It is not hard to show this conservation via \eqref{const function}. It can also be shown that these variables are canonical \eqref{cannonical 1}-\eqref{cannonical 3}.

We use our previous results to expand \(P_1\), \(P_2\), and \(P_3\) into orbital elements. \(P_1\) is the total energy of the system: \begin{equation} P_1=\frac{\mu}{2}\parallel\dot{\vec{r}}\parallel^2-\frac{\mathcal{G}\mu m}{r}=\mathcal{G}\mu m\left(\frac{1}{r}-\frac{1}{2a}\right)-\frac{\mathcal{G}\mu m}{r}=-\frac{\mathcal{G}\mu m}{2a} \end{equation} We have used \eqref{p def} and \eqref{v^2 equation}. To transform \(P_2\) and \(P_3\), we need to consider the angular momentum of the system. Recalling that \(L\equiv\mu\parallel\vec{r}\times\dot{\vec{r}}\parallel\) and using \eqref{polar transform end}-\eqref{polar transform end}: \begin{equation} L\equiv\parallel\vec{r}\times{\vec{p}}\parallel=\sqrt{p_\theta^2+\frac{p_\phi^2}{\sin^2{\theta}}}\quad\rightarrow\quad P_3=L \end{equation} Considering the \(z\) component of the angular momentum yields:

\[\begin{equation} \left(\vec{r}\times\vec{p}\right)_{z} = p_{\phi} = P_2 \end{equation}\]As \(L\) is the norm of the angular momentum, and the angular momentum of the system is normal to the orbital plane, the \(z\) component of the angular momentum is given by \(P_3=L\cos{I}\), a projection of the angular momentum onto the \(z\) axis. With \eqref{L defintion} in summary:

\begin{equation} P_1 = -\frac{\mathcal{G}\mu m}{2a} \label{P_1 def} \end{equation}

\begin{equation} P_3 = \mu \sqrt{\mathcal{G}ma\left(1 - e^2\right)} \label{P_3 def} \end{equation}

\begin{equation} P_2 = P_3 \cos{I} \label{P_2 def} \end{equation}

Having expressed our transformed momenta in orbital elements, we must do the same for our transformed position coordinates. We solve for \(S\) by integrating \eqref{S_t derivative}-\eqref{S_r derivative}:

\begin{equation} S=-P_1 t+P_2 \phi+\int\sqrt{P_3^2-\frac{P_2^2}{\sin^2\theta}}d\theta+\int\sqrt{2\mu P_1+\frac{2\mathcal{G}\mu^2 m}{r}-\frac{P_3^2}{r^2}}dr \end{equation}

Using \eqref{transormned position coordinates}:

\begin{equation} Q_1 = \frac{\partial {S}}{\partial P_1} = -t + \mu \int \frac{dr}{\sqrt{2\mu\left(P_1 + \frac{\mathcal{G}\mu m}{r}\right) - \frac{P_3^2}{r^2}}} = -t + \mu I_1 \end{equation}

\begin{equation} Q_2 = \frac{\partial {S}}{\partial P_2} = \phi - P_2 \int \frac{d\theta}{\sin^2\theta\sqrt{P_3^2 - \frac{P_2^2}{\sin^2\theta}}} = \phi - P_2 I_3 \end{equation}

\begin{equation} Q_3 = \frac{\partial {S}}{\partial P_3} = P_3 \int \frac{d\theta}{\sqrt{P_3^2 - \frac{P_2^2}{\sin^2\theta}}} - P_3 \int \frac{dr}{r^2 \sqrt{2\mu \left(P_1 + \frac{\mathcal{G}\mu m}{r}\right) - \frac{P_3^2}{r^2}}} = P_3\left(I_4 - I_2\right) \end{equation}

Evaluating the integrals in order, starting with \(I_1\). With \eqref{P_1 def} and \eqref{P_3 def}:

\begin{equation} I_1=\frac{1}{\mu\sqrt{\mathcal{G}m}}\int\frac{rdr}{\sqrt{-\frac{r^2}{a}+2r-a\left(1-e^2\right)}} \end{equation}

With \eqref{r E equation}, \(dr=ae\sin EdE\), and \(I_1\) becomes:

\begin{equation} I_1 = \frac{1}{\mu \sqrt{\mathcal{G}m}} \int \frac{a^2 e \left(1 - e \cos E\right) \sin E \, dE}{\sqrt{- a \left(1 - e \cos E\right)^2 + 2a \left(1 - e \cos E\right) - a \left(1 - e^2\right)}} \end{equation}

\begin{equation} = \frac{a^{\frac{3}{2}}}{\mu \sqrt{\mathcal{G}m}} \int \left(1 - e \cos E\right) dE \end{equation} Solving and plugging in \eqref{Kepler eq} \begin{equation} I_1=\frac{a^\frac{3}{2}}{\mu\sqrt{\mathcal{G}m}}\left(E-e\sin E\right)=\frac{\mathcal{M}}{\mu n} \end{equation}

Now for \(I_2\), with the same substitutions:

\begin{equation} I_2 = \frac{1}{\mu \sqrt{\mathcal{G}m}} \int \frac{dr}{r \sqrt{-\frac{r^2}{a} + 2r - a\left(1 - e^2\right)}} \end{equation}

\begin{equation} = \frac{1}{\mu \sqrt{\mathcal{G}m}} \int \frac{e \sin E \, dE}{\left(1 - e \cos{E}\right) \sqrt{- a \left(1 - e \cos E\right)^2 + 2a \left(1 - e \cos E\right) - a \left(1 - e^2\right)}} \end{equation}

\begin{equation} = \frac{1}{\mu \sqrt{\mathcal{G}ma}} \int \frac{dE}{1 - e \cos{E}} \end{equation}

Now, with \eqref{cos f equation}:

\begin{equation} \cos{f} = \frac{a}{r} \left( \cos{E} - e \right) = \frac{\cos{E} - e}{1 - e \cos E} \end{equation}

\begin{equation} \sin{f} = \sqrt{1 - \cos^2 f} = \sqrt{1 - e^2} \frac{\sin E}{1 - e \cos E} \end{equation}

\begin{equation} -\sin f \, df = \frac{\left(e^2 - 1\right) \sin E}{\left(1 - e \cos E\right)^2} \, dE \quad \rightarrow \quad df = \frac{\sqrt{1 - e^2}}{1 - e \cos E} \, dE \end{equation}

Thus, \(I_2\) becomes:

\begin{equation} I_2=\frac{1}{\mu\sqrt{\mathcal{G}ma\left(1-e^2\right)}}\int df=\frac{f}{P_3} \end{equation} Now for \(I_3\). With \eqref{P_2 def} and \eqref{P_3 def}: \begin{equation} I_3=\frac{1}{P_2}\int\frac{\cos Id\theta}{\sin^2\theta\sqrt{1-\frac{\cos^2 I}{\sin^2\theta}}} \end{equation}

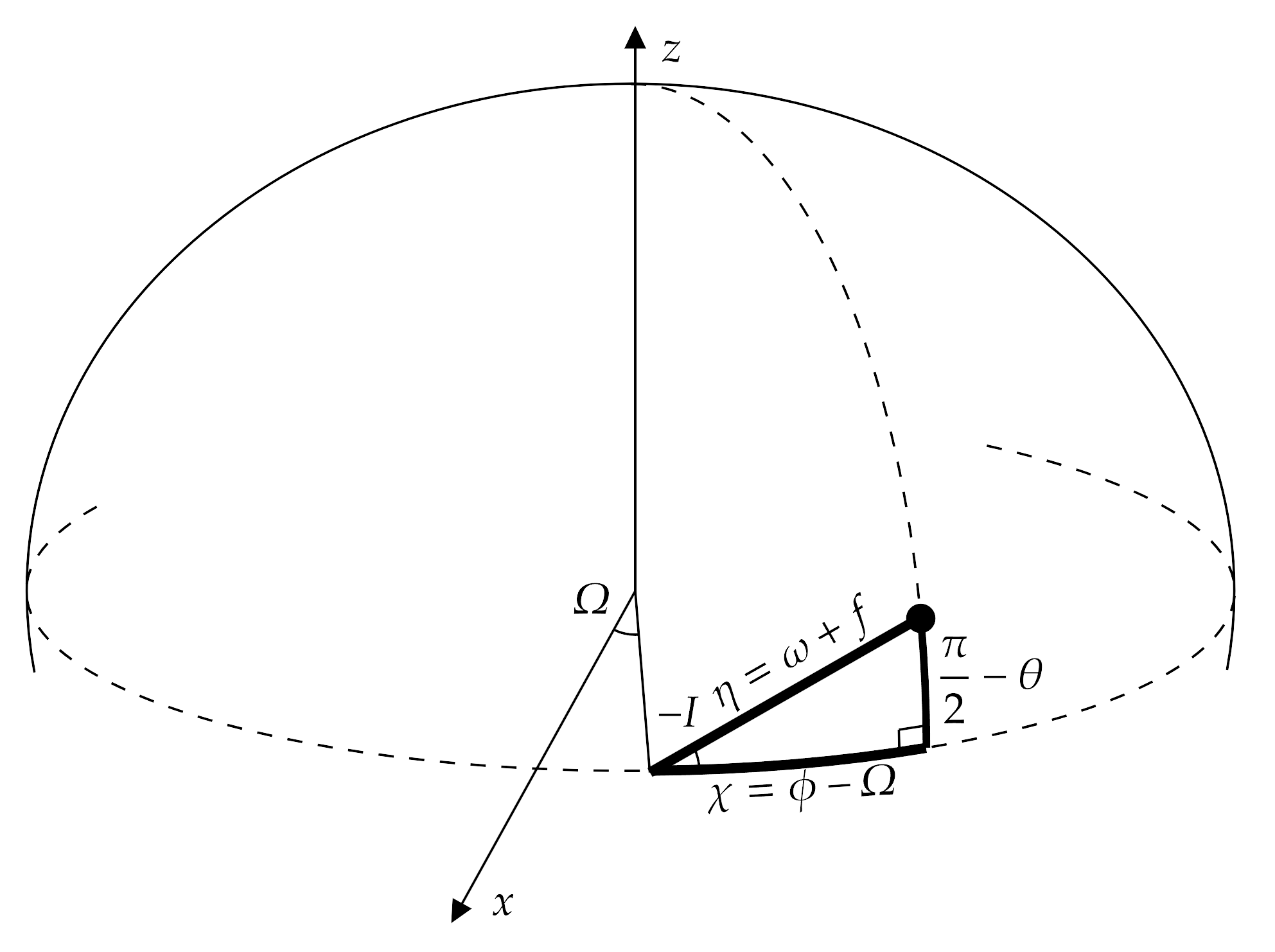

To proceed, we must consult spherical trigonometric relationships. We plot the angle created by the body’s position on the orbital plane and the reference plane. Because \(\theta\) is measured from the \(z\) axis towards the reference plane, we must invert \(I\).

From spherical trigonometric relations: \begin{equation} \tan{\left(\frac{\pi}{2}-\theta\right)}=\tan{-I}\sin{\chi}\label{sphere_trig tan} \end{equation} \begin{equation} \sin{\left(\frac{\pi}{2}-\theta\right)}=\sin{-I}\sin{\eta}\label{sphere_trig sin} \end{equation} From \eqref{sphere_trig tan}: \begin{equation} \cot{\theta}=-\tan{I}\sin{\chi}\quad\rightarrow\quad\csc^2\theta d\theta=\tan{I}\cos{\chi}d\chi \end{equation} \begin{equation} \csc^2\theta=1+\cot^2{\theta}=1+\tan^2{I}\sin^2{\chi} \end{equation} \(I_3\) becomes: \begin{equation} I_3=\frac{1}{P_2}\int\frac{\cos I\tan{I}\cos{\chi}d\chi}{\sqrt{1-\cos^2 I\left(1+\tan^2{I}\sin^2{\chi}\right)}} \end{equation} \begin{equation} =\frac{1}{P_2}\int d\chi=\frac{\chi}{P_2} \end{equation} And for the final integral, \(I_4\), repeating the process as in \(I_3\): \begin{equation} I_4=\frac{1}{P_3}\int\frac{\sin\theta d\theta}{\sqrt{\sin^2\theta-\cos^2 I}} \end{equation} With \eqref{sphere_trig sin}: \begin{equation} \cos{\theta}=\sin{-I}\sin{\eta}\quad\rightarrow\quad\sin{\theta}d\theta=\sin{I}\cos{\eta}d\eta \end{equation} \begin{equation} \sin^2{\theta}=1-\cos^2\theta=1-\sin^2{I}\sin^2{\eta} \end{equation} \(I_4\) becomes: \begin{equation} I_4=\frac{1}{P_3}\int\frac{\sin{I}\cos{\eta}d\eta}{\sqrt{1-\sin^2{I}\sin^2{\eta}-\cos^2 I}}=\frac{1}{P_3}\int d\eta=\frac{\eta}{P_3} \end{equation}

We can now evaluate our transformed coordinates:

\begin{equation} Q_1 = -t + \frac{\mathcal{M}}{n} = -t_0 \end{equation}

\begin{equation} Q_2 = \phi - \chi = \Omega \end{equation}

\begin{equation} Q_3 = \eta - f = \omega \end{equation}

Together with \(P_1\), \(P_2\), and \(P_3\) we have completed our canonical transform. We perform one more transformation, \(Q_i\rightarrow g,h,l\), and \(P_i\rightarrow G,H,L\) to make our coordinate system slightly more convenient. Let our generating function be:

\begin{equation} S\left(Q_1,Q_2,Q_3;G,H,L;t\right)=\left(nL-\frac{3\mathcal{G}\mu m}{2a}\right)\left(t+Q_1\right)+HQ_2+GQ_3 \end{equation}

From our canonical transform:

\begin{equation} P_1 = \frac{\partial S}{\partial Q_1} = nL - \frac{3\mathcal{G}\mu m}{2a} \quad\rightarrow\quad L = \frac{\mathcal{G}\mu m}{an} = \mu \sqrt{\mathcal{G}ma} \end{equation}

\begin{equation} P_3 = \frac{\partial S}{\partial Q_3} = G \quad\rightarrow\quad G = L \sqrt{1 - e^2} \end{equation}

\begin{equation} P_2 = \frac{\partial S}{\partial Q_2} = H \quad\rightarrow\quad H = G \cos{I} \end{equation}

\begin{equation} l = \frac{\partial S}{\partial L} = n \left( t + Q_1 \right) = \mathcal{M} \end{equation}

\begin{equation} g = \frac{\partial S}{\partial G} = Q_3 = \omega \end{equation}

\begin{equation} h = \frac{\partial S}{\partial H} = Q_2 = \Omega \end{equation}

These are called Delaunay Variables, and including the transformed Hamiltonian \(\mathcal{K}\), we summarize:

\begin{equation} L = \mu \sqrt{\mathcal{G}ma} \end{equation}

\begin{equation} G = L \sqrt{1 - e^2} \end{equation}

\begin{equation} H = G \cos{I} \end{equation}

\begin{equation} l = \mathcal{M} \end{equation}

\begin{equation} g = \omega \end{equation}

\begin{equation} h = \Omega \end{equation}

\begin{equation} \mathcal{K} = -\frac{\mathcal{G}^2 \mu^3 m^2}{2L^2} \label{2 body delauny hamiltonian} \end{equation}

Of our six coordinates, only \(l\) changes in time. As \(e\rightarrow 1\) and \(I\rightarrow 0\), \(g\), and \(h\) become ill-defined, which we can correct by another canonical transform to Modified Delaunay Variables. Using the generating function: \begin{equation} S\left(l,g,h;\Lambda,P,Q;t\right)=\left(l+g+h\right)\Lambda-\left(g+h\right)P-hQ \end{equation} We find the new set of coordinates, \(\Lambda\), \(P\), \(Q\), \(\lambda\), \(p\), and \(q\):

\begin{equation} \Lambda = L = \mu \sqrt{\mathcal{G}ma} \end{equation}

\begin{equation} P = L - G = \Lambda \left( 1 - \sqrt{1 - e^2} \right) \end{equation}

\begin{equation} Q = G - H = 2 \left( \Lambda - P \right) \sin^2 \frac{I}{2} \end{equation}

\begin{equation} \lambda = l + g + h = \mathcal{M} + \varpi \end{equation}

\begin{equation} p = -g - h = -\varpi \end{equation}

\begin{equation} q = -h = -\Omega \end{equation}

We have defined the longitude of the periapis: \(\varpi\equiv\omega+\Omega\). The advantage here is that \(\lambda\) is always defined, and \(p\) and \(q\) are only ill-defined when their corresponding momenta \(P\) and \(Q\) are equal to zero.

V. The Three-Body Hamiltonian and the Lagrange Planetary Equations

Now we approach the three-body problem by considering a perturbation to the two-body Hamiltonian: \begin{equation} \mathcal{H}=-\frac{\mathcal{G}^2\mu_1^3m_1^2}{2\Lambda_1^2}+\mathcal{R}\left(\Lambda_1,…\right) \end{equation} Where \(\mathcal{R}\) is the disturbing function, written in terms of the six modified Delaunay variables. We have adopted a new notation for the total and reduced masses, denoting: \(m_i=m_0'+m_i'\), \(\mu_i=\frac{m_0'm_i'}{m_0'+m_i'}\). The equations of motion are easy to calculate:

\begin{equation} \dot{\Lambda}_i = - \frac{\partial \mathcal{R}}{\partial \lambda_i} \label{Delaunay Lagrange 1} \end{equation}

\begin{equation} \dot{P}_i = - \frac{\partial \mathcal{R}}{\partial p_i} \end{equation}

\begin{equation} \dot{Q}_i = - \frac{\partial \mathcal{R}}{\partial q_i} \end{equation}

\begin{equation} \dot{\lambda}_i = \frac{\mathcal{G}^2 \mu_1^3 m_i^2}{\Lambda_i^3} + \frac{\partial \mathcal{R}}{\partial \Lambda_i} \end{equation}

\begin{equation} \dot{p}_i = \frac{\partial \mathcal{R}}{\partial P_i} \end{equation}

\begin{equation} \dot{q}_i = \frac{\partial \mathcal{R}}{\partial Q_i} \label{Delaunay Lagrange 2} \end{equation}

\eqref{Delaunay Lagrange 1}-\eqref{Delaunay Lagrange 2} are the Lagrange Planetary Equations, and we can rewrite these in terms of our orbital elements: \(a\), \(e\), \(\lambda\), \(\varpi\), \(\Omega\), and \(I\).

First expressing \(a\), \(e\), and \(e\) in terms of Delaunay variables:

\begin{equation} a_i = \frac{\Lambda_i^2}{\mathcal{G} \mu_i^2 m_i} \end{equation}

\begin{equation} e_i = \sqrt{1 - \left( 1 - \frac{P_i}{\Lambda_i} \right)^2} \end{equation}

\begin{equation} \sin{\frac{I_i}{2}} = \sqrt{\frac{Q_i}{2 \left( \Lambda_i - P_i \right)}} \end{equation}

Calculating the partial derivatives of the disturbing function:

\begin{equation} \dot{\Lambda}_i = \frac{\partial \Lambda_i}{\partial a_i} \dot{a}_i \label{orbital convert 1} \end{equation}

\begin{equation} = \frac{\mu_i \sqrt{\mathcal{G} m_i}}{2 \sqrt{a_i}} \dot{a}_i\nonumber \end{equation}

\begin{equation} \dot{P}_i = \frac{\partial P_i}{\partial a_i} \dot{a}_i + \frac{\partial P_i}{\partial e_i} \dot{e}_i \end{equation}

\begin{equation} = \frac{\mu_i \sqrt{\mathcal{G} m_i}}{2 \sqrt{a_i}} \left( 1 - \sqrt{1 - e_i^2} \right) \dot{a}_i + \frac{\mu_i \sqrt{\mathcal{G} m_i a_i}}{\sqrt{1 - e_i^2}} e_i \dot{e}_i\nonumber \end{equation}

\begin{equation} \dot{Q}_i = \frac{\partial Q_i}{\partial a_i} \dot{a}_i + \frac{\partial Q_i}{\partial e_i} \dot{e}_i + \frac{\partial Q_i}{\partial I_i} \dot{I}_i \end{equation}

\begin{equation} = \frac{\mu_i \sqrt{\mathcal{G} m_i}}{\sqrt{a_i}} \sqrt{1 - e_i^2} \sin^2 \frac{I_i}{2} \dot{a}_i - \frac{2 \mu_i \sqrt{\mathcal{G} m_i a_i}}{\sqrt{1 - e_i^2}} e_i \sin^2 \frac{I_i}{2} \dot{e}_i + \mu_i \sqrt{\mathcal{G} m_i a_i} \sqrt{1 - e_i^2} \sin I_i \dot{I}_i\nonumber \end{equation}

\begin{equation} \frac{\partial \mathcal{R}}{\partial \Lambda_i} = \frac{\partial \mathcal{R}}{\partial a_i} \frac{da_i}{d\Lambda_i} + \frac{\partial \mathcal{R}}{\partial e_i} \frac{de_i}{d\Lambda_i} + \frac{\partial \mathcal{R}}{\partial I_i} \frac{dI_i}{d\Lambda_i} \end{equation}

\begin{equation} = \frac{2a_i}{\mu_i \sqrt{\mathcal{G} m_i a_i}} \frac{\partial \mathcal{R}}{\partial a_i} + \frac{1 - e_i^2 - \sqrt{1 - e_i^2}}{\mu_i e_i \sqrt{\mathcal{G} m_i a_i}} \frac{\partial \mathcal{R}}{\partial e_i} - \frac{\tan \frac{I_i}{2}}{\mu_i \sqrt{\mathcal{G} m_i a_i} \sqrt{1 - e_i^2}} \frac{\partial \mathcal{R}}{\partial I_i}\nonumber \end{equation}

\begin{equation} \frac{\partial \mathcal{R}}{\partial P_i} = \frac{\partial \mathcal{R}}{\partial e_i} \frac{de_i}{dP_i} + \frac{\partial \mathcal{R}}{\partial I_i} \frac{dI_i}{dP_i} \end{equation}

\begin{equation} = \frac{\sqrt{1 - e_i^2}}{\mu_i e_i \sqrt{\mathcal{G} m_i a_i}} \frac{\partial \mathcal{R}}{\partial e_i} + \frac{\tan \frac{I_i}{2}}{\mu_i \sqrt{\mathcal{G} m_i a_i} \sqrt{1 - e_i^2}} \frac{\partial \mathcal{R}}{\partial I_i}\nonumber \end{equation}

\begin{equation} \frac{\partial \mathcal{R}}{\partial Q_i} = \frac{\partial \mathcal{R}}{\partial I_i} \frac{dI_i}{dQ_i} \label{orbital convert end} \end{equation}

\begin{equation} = \frac{1}{\mu_i \sqrt{\mathcal{G} m_i a_i} \sin I_i \sqrt{1 - e_i^2}} \frac{\partial \mathcal{R}}{\partial I_i}\nonumber \end{equation}

And combining \eqref{Delaunay Lagrange 1}-\eqref{Delaunay Lagrange 2} with \eqref{orbital convert 1}-\eqref{orbital convert end}:

\begin{equation} \dot{a}_i = -\frac{2 \sqrt{a_i}}{\mu_i \sqrt{\mathcal{G} m_i}} \frac{\partial \mathcal{R}}{\partial \lambda_i} \label{lagrange start} \end{equation}

\begin{equation} \dot{e}_i = - \frac{1 - e_i^2 - \sqrt{1 - e_i^2}}{\mu_i e_i \sqrt{\mathcal{G} m_i a_i}} \frac{\partial \mathcal{R}}{\partial \lambda_i} + \frac{\sqrt{1 - e_i^2}}{\mu_i e_i \sqrt{\mathcal{G} m_i a_i}} \frac{\partial \mathcal{R}}{\partial \varpi_i} \end{equation}

\begin{equation} \dot{I}_i = \frac{\tan \frac{I_i}{2}}{\mu_i \sqrt{\mathcal{G} m_i a_i} \sqrt{1 - e_i^2}} \frac{\partial \mathcal{R}}{\partial \lambda_i} + \frac{\tan \frac{I_i}{2}}{\mu_i \sqrt{\mathcal{G} m_i a_i} \sqrt{1 - e_i^2}} \frac{\partial \mathcal{R}}{\partial \varpi_i} + \frac{1}{\mu_i \sqrt{\mathcal{G} m_i a_i} \sin I_i \sqrt{1 - e_i^2}} \frac{\partial \mathcal{R}}{\partial \Omega_i} \end{equation}

\begin{equation} \dot{\lambda}_i = \frac{\sqrt{\mathcal{G} m_i}}{a_i^{\frac{3}{2}}} + \frac{2 a_i}{\mu_i \sqrt{\mathcal{G} m_i a_i}} \frac{\partial \mathcal{R}}{\partial a_i} + \frac{1 - e_i^2 - \sqrt{1 - e_i^2}}{\mu_i e_i \sqrt{\mathcal{G} m_i a_i}} \frac{\partial \mathcal{R}}{\partial e_i} - \frac{\tan \frac{I_i}{2}}{\mu_i \sqrt{\mathcal{G} m_i a_i} \sqrt{1 - e_i^2}} \frac{\partial \mathcal{R}}{\partial I_i} \end{equation}

\begin{equation} \dot{\varpi}_i = - \frac{\sqrt{1 - e_i^2}}{\mu_i e_i \sqrt{\mathcal{G} m_i a_i}} \frac{\partial \mathcal{R}}{\partial e_i} - \frac{\tan \frac{I_i}{2}}{\mu_i \sqrt{\mathcal{G} m_i a_i} \sqrt{1 - e_i^2}} \frac{\partial \mathcal{R}}{\partial I_i} \label{varpi evolve} \end{equation}

\begin{equation} \dot{\Omega}_i = - \frac{1}{\mu_i \sqrt{\mathcal{G} m_i a_i} \sin I_i \sqrt{1 - e_i^2}} \frac{\partial \mathcal{R}}{\partial I_i} \label{lagrange end} \end{equation}

We have arrived at the Lagrange Planetary Equations. Note that these expressions are entirely independent of the form of the disturbing function \(\mathcal{R}\) and we have taken no simplifying or approximating steps during our derivation.

Finally, we approximate \eqref{lagrange start}-\eqref{lagrange end} to second order for small \(e_i\) and \(I_i\):

\begin{equation} \dot{e}_i \simeq \frac{1}{\mu_i e_i \sqrt{\mathcal{G} m_i a_i}} \frac{\partial \mathcal{R}}{\partial \varpi_i} \label{lagrange simple start} \end{equation}

\begin{equation} \dot{I}_i \simeq \frac{1}{\mu_i I_i \sqrt{\mathcal{G} m_i a_i}} \frac{\partial \mathcal{R}}{\partial \Omega_i} \end{equation}

\begin{equation} \dot{\varpi}_i \simeq - \frac{1}{\mu_i e_i \sqrt{\mathcal{G} m_i a_i}} \frac{\partial \mathcal{R}}{\partial e_i} \end{equation}

\begin{equation} \dot{\Omega}_i \simeq - \frac{1}{\mu_i \sqrt{\mathcal{G} m_i a_i} I_i} \frac{\partial \mathcal{R}}{\partial I_i} \label{lagrange simple end} \end{equation}

In this approximation, \(a_1\) is constant as it varies much slower than the other orbital elements. Similarly, \(\lambda_i\) varies in time only from the non-perturbed element, independent of \(\mathcal{R}\). It is convenient to define a few additional variables:

\begin{equation} h_i \equiv e_i \sin \varpi_i \label{orbital vector start} \end{equation}

\begin{equation} k_i \equiv e_i \cos \varpi_i \end{equation}

\begin{equation} p_i \equiv I_i \sin \Omega_i \end{equation}

\begin{equation} q_i \equiv I_i \cos \Omega_i \label{orbital vector end} \end{equation}

Rewriting \eqref{lagrange simple start}-\eqref{lagrange simple end} with our new variables:

\begin{equation} \dot{h}_i = \frac{\partial h_i}{\partial e_i} \dot{e}_i + \frac{\partial h_i}{\partial \varpi_i} \dot{\varpi}_i \simeq - \frac{1}{\mu_i \sqrt{\mathcal{G} m_i a_i}} \frac{\partial \mathcal{R}}{\partial k_i} \label{simplified lagrange start} \end{equation}

\begin{equation} \dot{k}_i = \frac{\partial k_i}{\partial e_i} \dot{e}_i + \frac{\partial k_i}{\partial \varpi_i} \dot{\varpi}_i \simeq \frac{1}{\mu_i \sqrt{\mathcal{G} m_i a_i}} \frac{\partial \mathcal{R}}{\partial h_i} \end{equation}

\begin{equation} \dot{p}_i = \frac{\partial p_i}{\partial I_i} \dot{I}_i + \frac{\partial p_i}{\partial \Omega_i} \dot{\Omega}_i \simeq - \frac{1}{\mu_i \sqrt{\mathcal{G} m_i a_i}} \frac{\partial \mathcal{R}}{\partial q_i} \end{equation}

\begin{equation} \dot{q}_i = \frac{\partial q_i}{\partial I_i} \dot{I}_i + \frac{\partial q_i}{\partial \Omega_i} \dot{\Omega}_i \simeq \frac{1}{\mu_i \sqrt{\mathcal{G} m_i a_i}} \frac{\partial \mathcal{R}}{\partial p_i} \label{simplified lagrange end} \end{equation}

The simplified form of our planetary equations, \eqref{simplified lagrange start}-\eqref{simplified lagrange end} will be convenient after expanding \(\mathcal{R}\) to second order in our orbital elements.

Sources

These notes a conglomeration of several derivations, I mainly followed Fitzpatrick’s 2012 book:

Fitzpatrick R. An Introduction to Celestial Mechanics. Cambridge University Press; 2012.

But I also consulted a few other sources including

Modern celestial mechanics : aspects of solar system dynamics, by Alessandro Morbidelli. London: Taylor & Francis, 2002, ISBN 0415279399

Methods of celestial mechanics. Vol. I, Gerhard Beutler. In cooperation with Leos Mervart and Andreas Verdun. Astronomy and Astrophysics Library. Berlin: Springer, ISBN 3-540-40749-9, 2005

Murray CD, Dermott SF. Solar System Dynamics. Cambridge University Press; 2000.